Romeo Castellucci and Teodor Currentzis return to Salzburg for an unusual programme: Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle coupled with De temporum fine comoedia by Carl Orff — two works that in formal terms seem complete opposites.

A pinnacle of early 20th-century musical theatre, Bluebeard’s Castle was composed to a text by Béla Balázs in 1911. The story of Bluebeard has its literary archetype in Charles Perrault’s fairy tales and tells of a wife-murderer who forbids his latest wife, who is driven by curiosity, to open a door behind which he has hidden his previous victims. Bartók’s opera develops entirely out of the dialogue between the two protagonists, Bluebeard and Judith, revealing an approach to the drama as a kind of spiritual and emotional force field. ‘Where is the stage: outside or within?’, as the prologue puts it, an invitation to the audience to ask themselves questions about the enigmatic nature of theatre as an allusive reverberation of the real.

Judith has left her parents and the man who loved her in order to be Bluebeard’s wife. He leads her into his dark, windowless castle — a stone dwelling, yet at the same time a sentient space that weeps, quakes and groans, and which has seven locked doors. The young wife wants to know what the forbidden chambers contain, wishing to fill them with light and warmth. Although Bluebeard tries to dissuade her, Judith demands the keys and opens one door after the next: there she sees instruments of torture, weapons, treasures, jewellery, a garden — and everywhere she discovers alarming traces of blood. The seventh door finally reveals Bluebeard’s previous wives, clothed in rich attire: the wives of the Dawn, Noon and Dusk. Decked with jewels and swathed in a cloak of stars, Judith becomes the wife of the Night. The concentrated action, lack of spatio-temporal coordinates and the mysterious atmosphere indicate a journey that takes place entirely within.

By contrast, the subject of De temporum fine comoedia is the Last Judgement, in a reinterpretation rooted in Carl Orff’s personal religious beliefs. The writing of the text in Ancient Greek, Latin and German took the composer a wholedecade, from 1960 to 1970, with the essence of the work being increasingly determined by the apocalyptic vision of the Alexandrian theologian Origen, in which at the end of time even demons will be granted forgiveness and salvation.

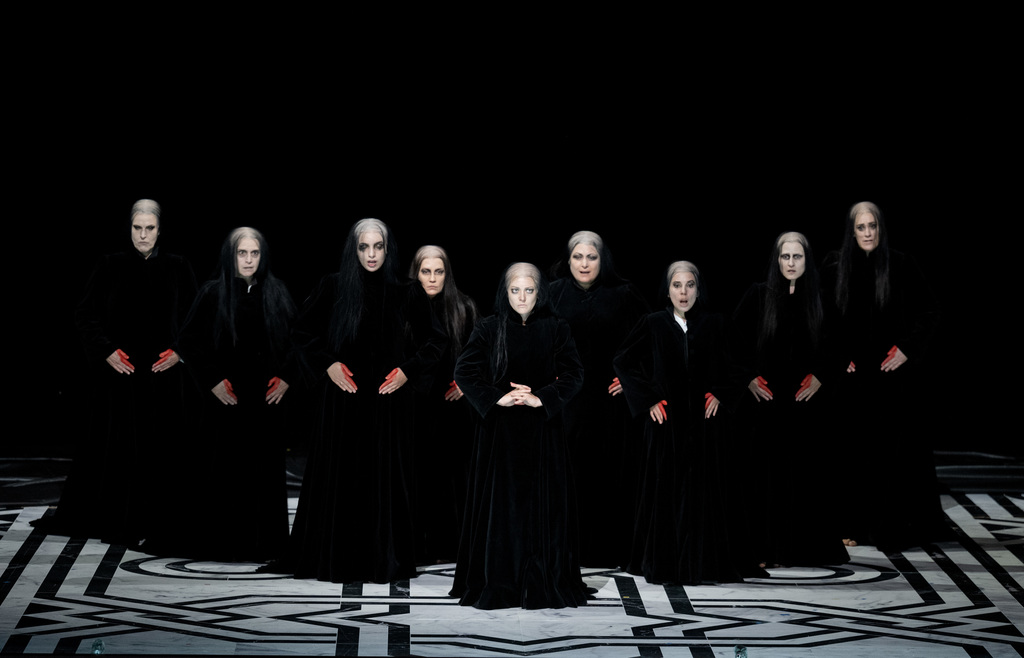

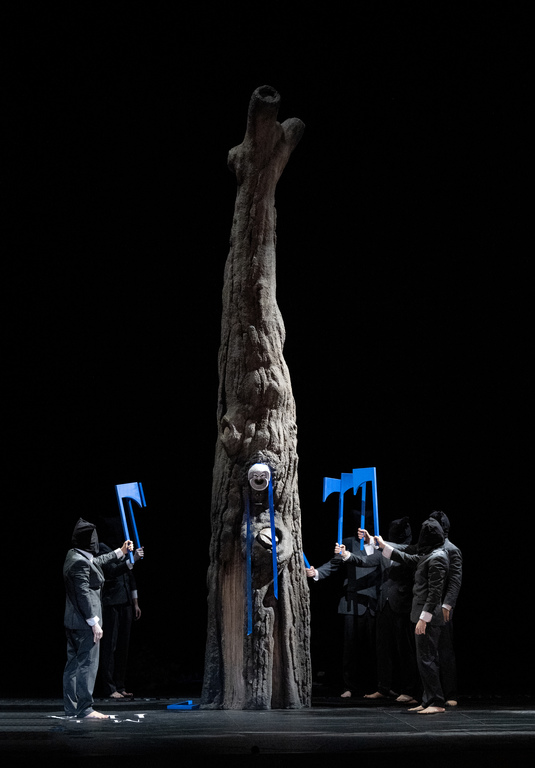

In the first part of the Comoedia nine Sibyls announce the imminent end of the world and the eternal damnation of the godless. In the second part these prophecies are countered by an emphatic ‘No’ from nine Anchorites: the learned hermits have come to understand that the final day will dawn not as the triumph of a punitive God but as the absorption of evil into the divine. The redemption of all wrongs and the return of all beings to God reaches its climax in the third part in the retransformation of Lucifer into the ‘bringer of light’ that he once was. The fallen angel couches his plea for forgiveness in words from the parable of the prodigal son: ‘Pater peccavi.’

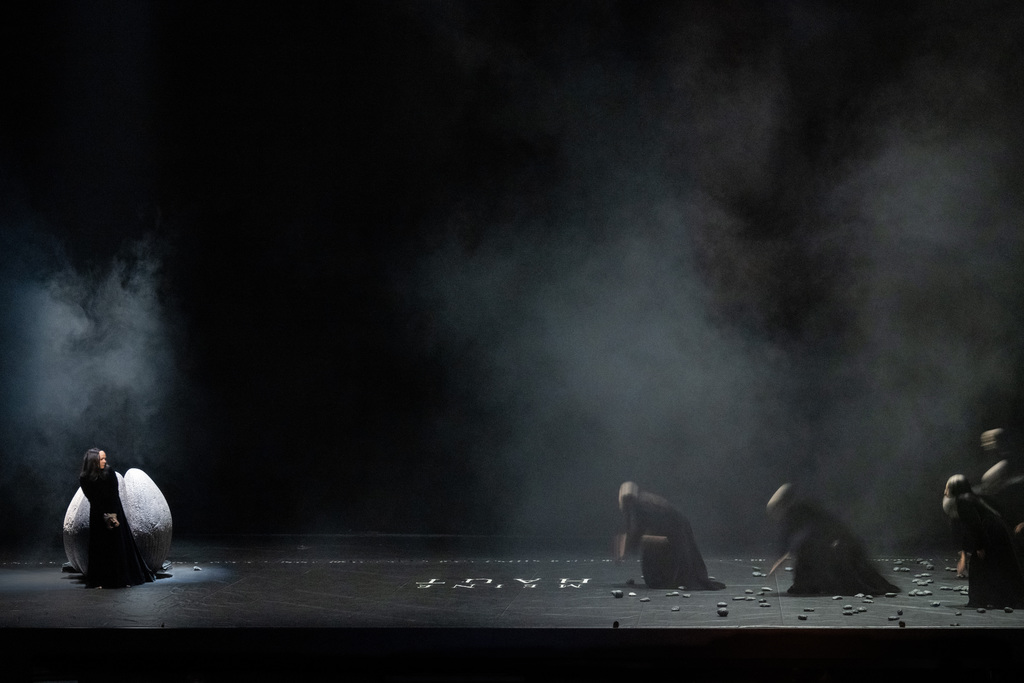

Brought to the Festival stage by Romeo Castellucci and Teodor Currentzis for the first time since its premiere in Salzburg in 1973, Orff’s opera-oratorio overwhelms the listener with its primeval energy. The latter results not least from persistently iterated rhythmic patterns that involve a host of figures animated by a mechanical principle of motion that will be translated into bodily movement scores by the choreographer Cindy Van Acker. The atmosphere that permeates Bluebeard’s Castle is diametrically opposed: Castellucci responds to the bleak intimacy of a drama without external action by focusing on Judith’s viewpoint — and on a trauma that unleashes a theatre of the psyche.

Concealed in the juxtaposition of the two works, between interiority and an explosion of violent power, are profound connections, as if the Day of Judgement has arrived for Judith, as if she herself had committed a crime…

Piersandra Di Matteo

Translation: Sophie Kidd